Soil pH plays a pivotal role in determining the health and productivity of crops. By understanding its dynamics and how it influences the availability of essential nutrients, farmers and gardeners can make informed decisions that lead to robust yields. This article delves into the science behind soil pH, outlines practical methods for assessment and correction, and explores crop-specific requirements as well as long-term management strategies.

Understanding Soil pH

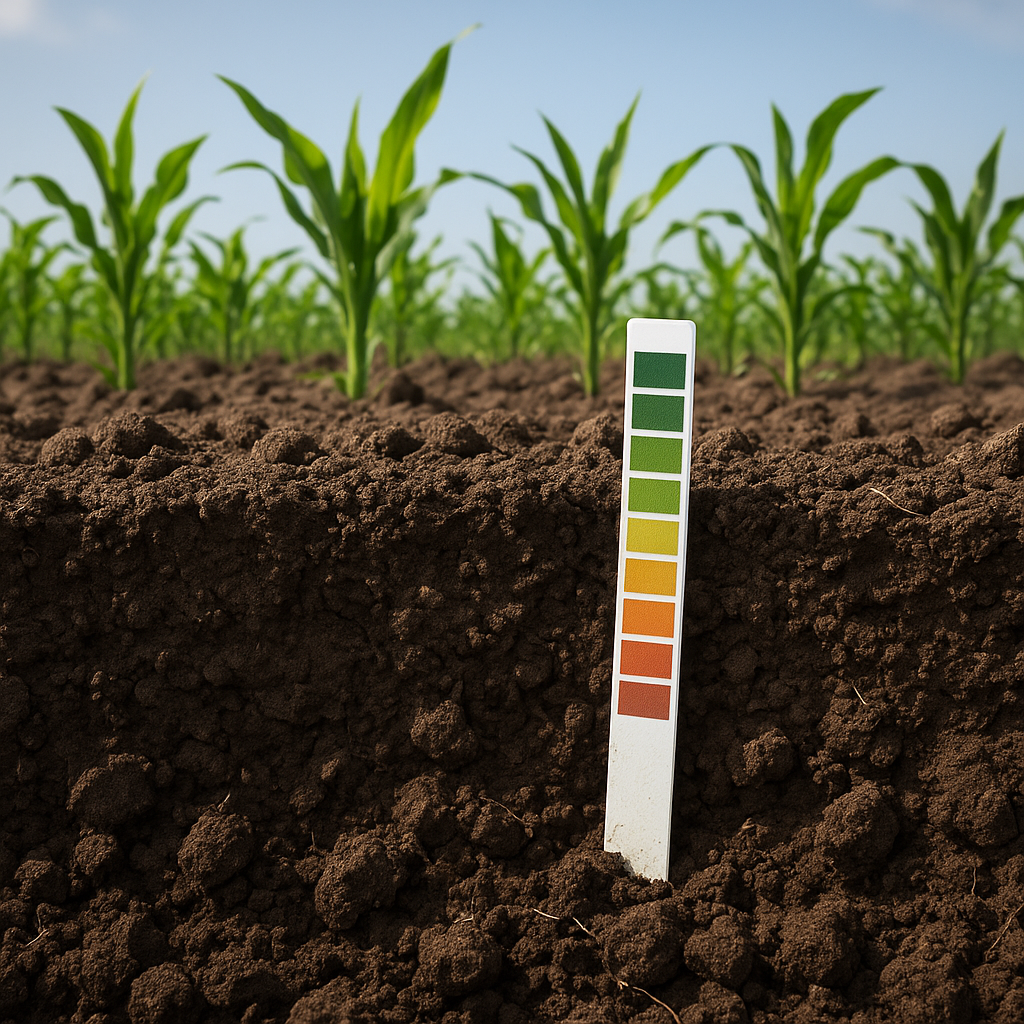

The pH scale measures how acidic or alkaline a soil solution is, ranging from 0 (highly acidic) to 14 (highly alkaline), with 7 being neutral. Most crops thrive in slightly acidic to neutral conditions—typically between pH 6.0 and 7.5. Deviations outside this range can hamper the plant’s ability to absorb critical nutrients, leading to stunted growth and lower crop yield.

The Chemistry Behind pH

- Hydrogen ions (H⁺): More H⁺ indicates acidity; fewer H⁺ indicates alkalinity.

- Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC): Soils with higher CEC hold more nutrients but may also buffer pH changes.

- Buffering capacity: The soil’s ability to resist pH changes depends on organic matter and clay content.

Effects on Nutrient Availability

Soil pH directly affects the solubility of minerals and metals. For example:

- In acidic soils (pH < 6.0), elements like aluminum and manganese can become toxic.

- In alkaline soils (pH > 7.5), iron, zinc, and phosphorus become less available.

Maintaining an optimal pH ensures balanced nutrient availability and fosters healthy microbial activity.

Measuring and Monitoring Soil pH

Accurate assessment is the first step toward effective pH management. Several methods are available:

- Soil test kits: Affordable and user-friendly, they provide quick field estimates.

- Laboratory analysis: Offers high precision and includes additional metrics such as organic carbon and EC.

- Electrochemical pH meters: Useful for instant readings in the field but require careful calibration.

Sampling Best Practices

- Take multiple cores from the root zone (6–8 inches deep).

- Combine samples from various locations to form a composite.

- Avoid sampling right after lime or fertilizer applications to prevent misleading results.

Frequency of Testing

Regular monitoring—at least once every 2–3 years—helps track trends and informs timely adjustments. Fields with known pH issues or intensive cropping systems may require annual testing.

Adjusting Soil pH for Optimal Crop Growth

Injecting corrective materials into the soil can shift pH to the desired range. Two primary amendments are used:

- Lime: Finely ground agricultural lime (calcium carbonate) raises pH by neutralizing H⁺.

- Sulfur: Elemental sulfur oxidizes to sulfuric acid, lowering soil pH.

Applying Lime

- Calculate requirement based on soil test recommendations and target pH.

- Incorporate lime evenly into the top 6 inches of soil for best results.

- Allow several months for full reaction; apply in the off-season when possible.

Using Sulfur

- Apply elemental sulfur at low rates to prevent sudden drops in pH.

- Combine with irrigation to enhance microbial oxidation.

- Monitor pH periodically, as sulfur can take weeks or months to fully react.

Other organic options include wood ash (raises pH) and peat moss (lowers pH), but their effects may vary and should be used with caution.

Crop-Specific pH Requirements

Different crops exhibit unique pH preferences. Understanding these patterns allows for targeted management and better yields.

Acid-Loving Crops

- Blueberries: Optimal at pH 4.5–5.5.

- Potatoes: Prefer pH 5.0–6.0 to limit scab-causing bacteria.

- Cranberries: Thrive between pH 4.0 and 5.0, often grown in raised beds with sphagnum moss.

Neutral-Range Crops

- Corn and Soybeans: Best at pH 6.0–7.0 for maximum nutrient uptake.

- Wheat: Grows well in pH 6.0–7.5 soils.

Alkaline-Tolerant Crops

- Beets and Spinach: Can tolerate pH up to 7.5.

- Quinoa: Adapts to pH 6.5–8.0 but may require micronutrient foliar sprays in very alkaline conditions.

Long-Term Soil pH Management

Maintaining stable pH involves integrated practices that improve overall soil health.

Incorporating Organic Matter

- Compost: Provides buffering capacity and releases nutrients slowly, helping stabilize pH swings.

- Cover crops: Legumes and grasses scavenge nutrients and, upon decomposition, add organic acids that can gently lower pH.

Irrigation Water Considerations

- High-bicarbonate water can lead to alkalinization over time.

- Periodic acidification of irrigation water (using diluted acid) may be necessary in very alkaline areas.

Rotation and Intercropping

Diverse cropping systems promote a wider range of root exudates and microbial populations, contributing to more consistent pH levels across seasons.

Monitoring Soil Biology

Healthy microbial communities enhance nutrient cycling and pH buffering. Practices such as reduced tillage and minimal chemical disturbance help sustain beneficial fungi and bacteria.

Advanced Techniques and Future Trends

Emerging technologies provide precise control over soil conditions:

- Sensor-based variable-rate lime and sulfur application using GPS-guided equipment.

- Real-time soil pH mapping with in-field probes and data analytics.

- Biological amendments, including specific microbial inoculants, designed to modulate pH through organic acid production.

Adopting such innovations can lead to more sustainable and profitable farming systems by optimizing the soil environment for every crop cycle.